The Covid-19 crisis is a time when you should gauge your family’s resilience—and build more of it. An enterprising family’s goal is to not just cope with adversity, but grow stronger as a result of it. Here are ways to achieve that.

The Covid-19 pandemic is a huge, disruptive event that is severely challenging every aspect of our societies, every level of our governments, and all sectors of our economies. This pandemic is a disorienting, strongly felt shock to our collective nervous system—a textbook case of a major crisis and setback. The health, societal, and economic upset from this disruption will rumble through the world for the rest of this year and into the next. The human, economic, and social costs of the pandemic are staggering, and the ultimate costs are only now being imagined. Some businesses will prosper during this period, but most will struggle, and no economy will be spared.

What will be the impact of the crisis on enterprising families?

There Are Two Possible Outcomes for a Family

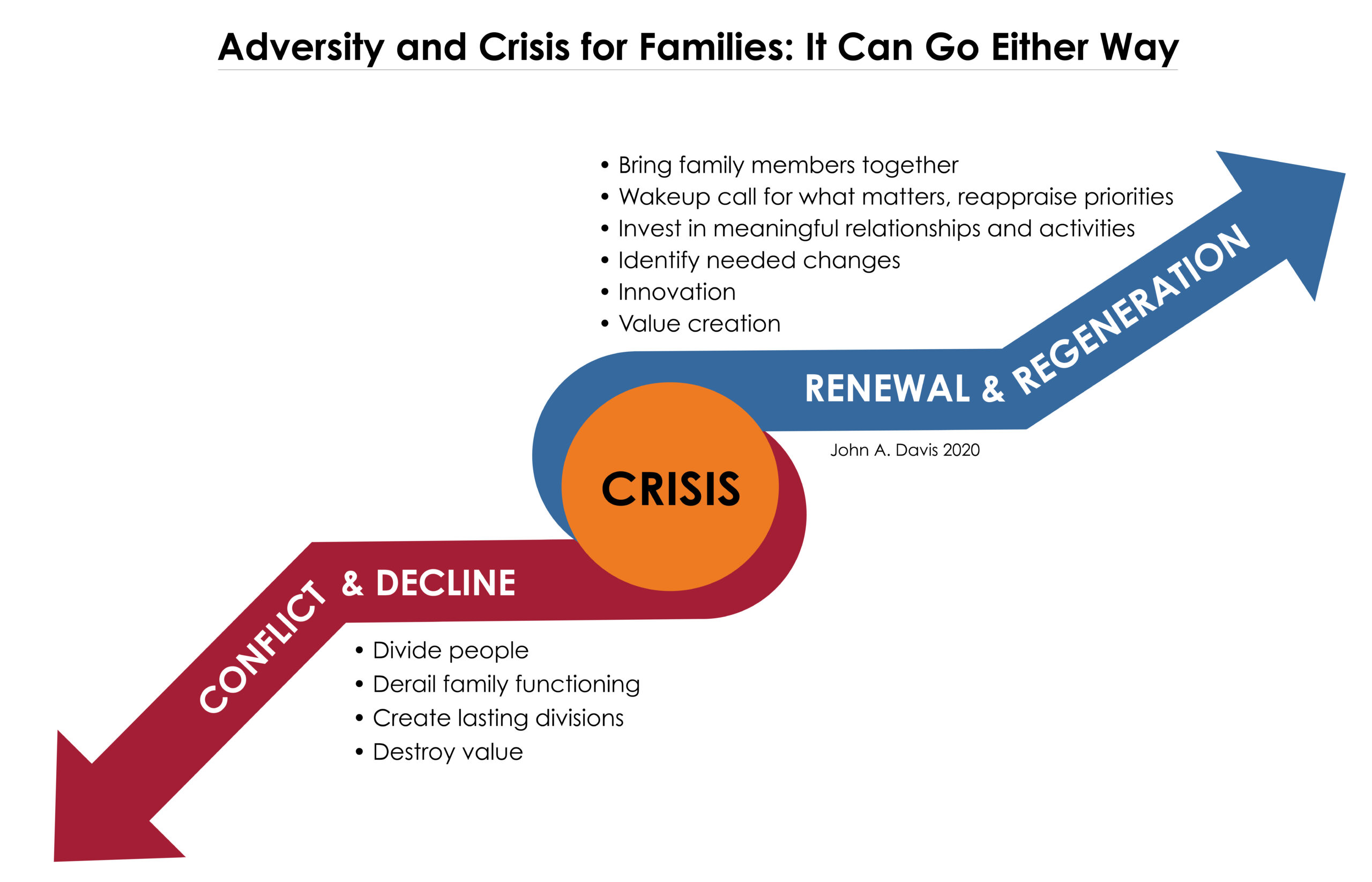

Adversity and crisis can either lead a family and its enterprise into decline, or into renewal and regeneration. It can go either way.

If you are not resilient, a crisis or prolonged adversity can more likely divide family members, derail family functioning and decision making, create lasting divisions, and destroy value.

If you are resilient, adversity will more often bring family members together, be a wakeup call for things that need to change, motivate more attention to meaningful relationships and activities, bring innovation to systems, and lead to reinvention and value creation.

Causes of Family Derailment

It’s easy to understand how crisis situations or periods of prolonged adversity can cause families or other groups to have difficulties. Crisis situations like we are in now can easily produce these outcomes:

Family members can feel considerable anxiety about their circumstances.

Some anxiety is needed to respond well to problems but too much anxiety paralyzes us or makes us aggressive. Great anxiety usually leads to more emotionally-reactive and self-protective behavior, and it is often associated with a loss of confidence, hiding from problems, rushing and staying busy but not solving critical problems, and looking for magic bullets, while tending to see a narrower scope of options. If you see these behaviors, as a leader you need to calmly but directly address them: reassure group members that these behaviors are understandable but not helpful or acceptable, and refocus family members on solving specific problems together.

Family members can experience loss and, understandably, fear that they will experience more loss.

People are experiencing a range of losses in this crisis–the loss of loved ones, of course, being the most profound. But it is not the only one: financial losses, loss of employment and income, loss of opportunities, loss of social interaction, loss of normalcy, loss of predictability, loss of control. Losses during this adverse time can raise old issues to the surface that can no longer be ignored. (In good times, money has a way of concealing problems.)

Typically, there are new crisis issues to manage that we may not be familiar with or feel capable to handle.

The combination of old and new issues can lead family members to feel a loss of control, resulting in the tendency to blame others. This results in conflicts, instead of pulling together.

The Key Determinant is Resilience

The key determinant of decline or regeneration (besides external forces and luck) is the presence or not of resilience in a group.

Resilience is the capability of an individual or group to get through and recover well from prolonged adversity, important setbacks, or crises. Resilience is created by having adequate resources, useful structures to support the family and make key decisions, and trusted leadership.

Think of resilience as a storehouse of these three types of ingredients:

Resources

- material resources to help cope with loss and maintain stability

- skills that are useful in a crisis or in a period of prolonged adversity (e.g. composure, courage, perseverance)

- experience solving tough problems while keeping members of your group united

- allies, advisors and friends who will help in a crisis

- a strong sense of purpose, trust, and pride in our family

- willpower and sense of hope to get through adversity, recover, and move forward again

- unity of family members, especially under pressure and conditions of deprivation

- family members who care for others, encourage them, and help them cope with loss

Leadership

- trusted leadership who can make wise, fair, tough decisions

- a leader who focuses our attention on needed accomplishments and encourages collaboration and problem solving

- a leader who conveys hope and purpose (why is it important to get through this)

Structures: Roles, Forums, Agreements, and Decision Processes

- clear roles for who decides, who is consulted, and who is informed of key information

- forums (like boards, family councils, owners’ councils) where groups can have important conversations and make key decisions

- decision rules, principles, and processes that help build consensus and help us make tough decisions

- ownership agreements and family policies that help maintain the stability of the group in hard times

>> I encourage you to do a quick assessment of the presence of each of these resilience ingredients in both your family and your family company.

Each of these resilience ingredients lowers anxiety in stressful times, encourages collaboration, and allows us to focus on important problems to be solved. Success through a crisis requires that these resilience ingredients work together to overcome hardship and achieve recovery.

Ideally, you should strengthen as many of these factors as you can before a crisis and be ready to re-energize any of these that weaken in adverse times. The weakest link in our arsenal (say, trust in other family members) can become overstressed and fray in hard times, then can stress other factors (like family unity and our material resources), which can further stress the system and eventually bring us down. System failures are usually the result of cascading and compounding smaller failures.

Resilience is Needed Today More than Ever

Around 2000, we entered a new age, which is ushering in more frequent and more volatile disruptions to industries, societies, companies, and families. It is common to describe today’s environment, borrowing from military parlance, as VUCA: Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous.

Accelerating changes in technology along with increased globalization has reshaped how commerce is done. Industries are changing, maturing, and disappearing much more quickly. Society is experiencing shifts such as increased diversity, increasing transparency, greater digital connectedness, and more political disruptions and social tensions. Scientific breakthroughs are increasing human lifespan and changing former genetic limitations. Business families themselves are morphing, becoming more diverse, more geographically dispersed, more international, and more egalitarian. The Millennials are changing the ways in which we do business, care for the world, and lead our lives. Add to these factors that societies, companies, and families must cope with periodic, widespread disruption such as the tragic Covid-19 pandemic.

In these conditions, companies must innovate constantly, anticipate disruption, and consider wider diversification to stay alive. The families behind these companies must themselves be innovative, agile, and resilient.

Resilient families and companies that get through the Coronavirus crisis will need then to get ready for the next disruption, and the next, because further disruptions are coming. Companies have heard this admonition for at least a decade, and progressive companies now consider how they can become more resilient and hopefully disruption-proof. A good part of my work today is helping family companies, family offices, and their owning families become better prepared for this new age, including growing more resilient.

Why Family Resilience?

We definitely need to build the resilience of the enterprising families behind family companies and family offices. The family is the ultimate foundation for a family enterprise—even more fundamental than the family owners.

The ability of a family business to survive long-term depends greatly on the ability of the family to:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- stay united, decisive, and industrious

- make important directional decisions for its business(es) and assets

- produce enough family talent to contribute in key ways to the family enterprise (e.g. as owners, wealth creators, board members, governance members, and in other ways)

- support adequate reinvestment in the company.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

If your family is not resilient, it will likely undermine the resilience of your ownership group and then your enterprise.

The good news is that a family and company that are able to successfully move through serious adversity will likely be better prepared for the next disruption. The family’s confidence, judgment, skills, unity, and pride will be strengthened and become embedded in its memory, giving the family or company a better chance to overcome the next setback it faces.

Help Your Family Develop Resilience

How resilient is your family? How does your family deal with prolonged adversity, setbacks or crisis? What are you doing to help your family learn from this period and grow in capability?

Your family’s goal should be not to just cope with the adversity it faces, but to grow stronger as a result of it. Your objective is that strengths come out of this struggle.

How do you achieve that? A family can build and reinforce resilience in good times and also during a crisis. In the midst of the current crisis, these actions will help:

- A family grows stronger as a unit by pulling together toward a common goal, supporting one another, and collaboratively problem-solving through hard times. Set previous disagreements aside. Don’t let them divide you in these times.

- Family leaders need to actively shepherd the family through this crisis: be open with the family about the challenges the family and its company face, give hope that both company and family will make it through this time, focus the family on specific concrete goals and actions, and stress the need for trust and collaboration.

- As much as you need strong performance during this time, emphasize the importance of behaving according to core family values. A family will be proud not just because it survived a crisis, but because it survived the crisis while keeping its values.

- Families need to know what, besides saving the family’s fortune, the family should try to accomplish in this crisis. Define what your family wants to protect and what its big goals are. Be open in this time to redefining how you achieve success as a family.

- Praise teamwork and support collaboration among family members. Challenge any attempts by some to achieve political advantage of the crisis for one faction or another in the family.

- Be a role model for future generations. An individual, a generation of the family, or the whole family can be a good role model for future generations regarding overcoming a crisis. Resilience is transmitted through the generations not only through successfully rebounding from adversity but also through role models. You learn from role models who acted bravely in crisis periods; they become memories that you will recall when you’re experiencing future challenges.

Resilience Builds on Itself

Getting through tough situations together as a family helps build the confidence, trust, pride, relationships, unity, and skills to face new challenges and rebound from the next crisis. Resilience builds on itself. It’s a virtuous cycle.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Resilience Assessment and Strengthener

Resilience Assessment and Strengthener

ASSESS YOUR FAMILY’S RESILIENCE

-

-

- How does your family deal with adversity?

- Which of the family resilience ingredients are abundant in your family? How are you reinforcing them?

- Which of the resilience ingredients are in short supply in your family? How can this crisis aggravate your weaknesses?

-

STRENGTHEN YOUR FAMILY’S RESILIENCE

-

-

- Which resilience ingredients can your family try to develop during the crisis?

- How can you organize your family to pull together in this crisis?

- How are family leaders guiding and focusing the family on getting through the crisis?

- Which of your family’s core values are you demonstrating and reinforcing in your crisis response?

- What are your family’s big goals to achieve in this crisis? Are you discussing these goals as a family?

- How well is your family supporting and championing one another and collaborating constructively to solve problems?

- Are you creating role models for future generations to learn how to navigate a crisis and rebound from it?

- Is the senior generation in your family talking with the next generation about how they’re approaching the crisis and what it takes to get through a tough period?

-

With an appreciative nod to Gabriel García Márquez and his literary classic, Love in the Time of Cholera. García Márquez teaches us all the value of persistence and resilience.