Originally published in: Exame (January 2014)

Campo Bom – O mineiro Alexandre Birman é um viciado em sapatos — os de salto agulha, de preferência. Enquanto executivos e empresários normais interrompem conversas para checar e-mails no telefone, Birman se distrai o tempo todo porque analisa os sapatos de cada mulher com quem cruza na rua, esbarra em eventos ou mesmo vê na televisão.

Essa espécie de distúrbio social começou a se manifestar aos 12 anos, quando presenteou o pai, Anderson, com um mocassim marrom feito, da concepção ao acabamento, por ele.

“Queria que meu pai nunca esquecesse, então caprichei”, diz Birman, que hoje comanda uma das maiores empresas de moda do Brasil, a sapataria Arezzo. A rigor, as origens de tanta obsessão remontam a 1972, quando o pai e o tio começaram a usar um galpão para fabricar sapatos e fundaram a empresa (o nome veio após uma pesquisa aleatória de cidades no mapa da Itália).

Alexandre nasceu quatro anos depois e cresceu dentro da fábrica, que teve um começo marcado pela modéstia. Com a Arezzo em dificuldades, ele contou com a ajuda do pai para fundar, aos 19 anos, sua própria marca de sapatos femininos, a Schutz. Nos 12 anos seguintes, pai e filho concorreram um com o outro.

Até que, em 2007, decidiram se unir novamente. Começou ali uma era de ouro para a Arezzo, que quintuplicou de tamanho desde então. Hoje, a empresa vale 2,6 bilhões de reais. Pai e filho figuram na lista de homens mais ricos do país, com uma fortuna de 1,7 bilhão de reais.

Não existe empresa de sapatos como a Arezzo. Alexandre Birman alimenta sua obsessão criando modelos num ritmo alucinado. Mais de 300 pessoas trabalham no centro de inovação da empresa, em Campo Bom, cidadezinha gaúcha a 60 quilômetros de Porto Alegre. Das pranchetas, saem 1 000 novos modelos de sapatos femininos por mês.

Birman coordena pessoalmente a triagem e escolhe os cerca de 170 modelos que chegam às prateleiras. Esse ritmo ajuda a explicar por que a Arezzo vende tanto. Separada em quatro marcas para públicos distintos, a Arezzo pode cobrar tanto 80 reais por uma sapatilha quanto 2 400 reais por uma sandália de couro de cobra. No ano passado, a empresa superou duas barreiras simbólicas.

Vendeu mais de 10 milhões de pares de sapatos e faturou 1 bilhão de reais. “Estamos investindo para virar uma das maiores empresas de sapatos do mundo”, diz Alexandre Birman, que, aos 37 anos, é o mais jovem entre os 100 executivos mais influentes do mundo do sapato.

A Arezzo é o símbolo de um fenômeno. Os brasileiros (mais precisamente, as brasileiras) nunca gastaram tanto dinheiro com sapatos, roupas, joias, óculos e os demais produtos que formam o que se convenciona chamar de mercado da moda. Em nenhum país, esse setor cresce tanto quanto no Brasil.

Nos últimos dez anos, o faturamento quadruplicou, e chegou a 140 bilhões de reais em 2013, segundo a consultoria Euromonitor. Nesse período, o mercado brasileiro saiu da 14a para a oitava posição entre os maiores do mundo — está prestes a passar o italiano, terra de grifes consagradas, como Prada, Gucci e Armani.

É uma trajetória que tem se repetido em outras áreas. O Brasil já é o maior consumidor mundial de perfumes, o segundo de produtos para cabelo, e o terceiro de cosméticos — atrás apenas de Estados Unidos e Japão. Era natural que o movimento se repetisse na moda. “Ainda há muito espaço para crescer”, diz Flávio Rocha, presidente da varejista de roupas Riachuelo, que cresceu 62% nos últimos cinco anos.

Pessoas com a cabeça no lugar só compram um sapato novo depois de assegurar que terão casa, comida e transporte (embora seja verdade que nem todos têm a cabeça no lugar). Por isso, o avanço da moda se dá aos saltos: de acordo com dados do Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE), as pessoas dobram seus gastos mensais com moda a cada degrau que sobem na escada social.

Nas classes D e E, quase todo o dinheiro é gasto em necessidades básicas, como moradia e alimentação. Sobram apenas 40 reais por mês para roupas e acessórios. Quem passa para a classe C gasta, em média, 97 reais. Na classe B, 202 reais. E, na classe A, 455 reais por mês.

Em outras categorias de produtos, a diferença de gastos por faixa de renda é muito menor. Portanto, à medida que um país enriquece e as pessoas pulam de faixa social, um dos setores mais beneficiados tende a ser o de moda. É o que vem acontecendo no Brasil.

Quem mais ajudou nessa expansão recente foram as mulheres. Mais de 11 milhões delas entraram no mercado de trabalho na última década, o que impulsiona o setor por dois motivos. Primeiro, e mais óbvio, porque têm mais dinheiro no bolso e, como mostram as estatísticas do IBGE, mais disposição para gastar.

Segundo, porque elas passam a ter a obrigação de andar mais bem vestidas no dia a dia. Esse tipo de mudança teve impacto direto em nichos como o de produtos para cabelo. E está se repetindo no vestuário. Segundo pesquisas da consultoria Data Popular, as mulheres das classes D e E têm em média nove pares de sapatos em casa. Nas classes A e B, a média sobe para 20.

Assim como aconteceu com a Arezzo, dezenas de empresas de moda mudaram de patamar com essa nova fase do mercado. Se historicamente as vendas de roupas se concentravam em lojinhas de bairro e grandes lojas que vendiam de tudo, a expansão do número de shoppings no país foi mudando a cara do setor — e abrindo espaço para quem queria criar marcas nacionais.

Segundo a consultoria do setor têxtil Iemi, a fatia de mercado das butiques de bairro caiu de 44% para 37% nos últimos seis anos. Enquanto isso, foram erguidos 160 shoppings no país na última década. Diversas empresas souberam aproveitar essa onda. O número de redes de franquias de moda avançou 259% no período.

Elas cresceram não só em número mas em tamanho. As redes de moda feminina Farm e Animale, que se uniram em 2010, crescem 35% ao ano e faturam 850 milhões de reais. A malharia catarinense Malwee, que vendia só para lojas de bairro, abriu mais de 100 pontos de venda desde 2011.

O grupo M5, dono da M. Officer, já tem 200 lojas. A rede de moda jovem TNG tem 180 lojas, todas próprias. Especialistas no setor calculam que existam perto de 50 empresas com faturamento de pelo menos 500 milhões de reais e que poderiam valer até 1 bilhão de reais caso fossem vendidas.

Nenhuma empresa aproveitou de forma tão ágil a oportunidade criada por esse novo momento quanto a camisaria catarinense Dudalina. Criada há 56 anos pelo casal Duda Souza e Adelina Hess, passou mais de cinco décadas vendendo suas camisas só para varejistas. Isso começou a mudar em 2010, quando abriu sua primeira loja-conceito.

Era o mesmo caminho seguido com sucesso pela pioneira Hering e as que vieram depois, como a Malwee e a Paquetá, fabricante de sapatos gaúcha que partiu para o varejo a fim de fugir da competição com os chineses. “Estava cansada de me sentir espremida pelo custo da matéria-prima e pela pressão por preço baixo dos lojistas”, afirma Sônia Hess, presidente da Dudalina e filha dos fundadores.

Naquele mesmo ano, a empresa começou a fabricar camisas femininas, feitas sob medida para o batalhão de mulheres que entravam no mercado de trabalho e ascendiam nas companhias. Na época, não havia uma varejista dedicada a esse público. O faturamento quadruplicou desde então, chegando a 500 milhões de reais em 2013.

Em dezembro, a família Hess vendeu 72% da Dudalina para os fundos de private equity americanos Advent e Warburg Pincus, numa transação que avaliou a empresa em 800 milhões de reais (a companhia não comenta esses dados). Com o fôlego financeiro dos fundos, a meta é chegar a 1 bilhão de reais em vendas em 2016. Para isso, passou de nove para 20 coleções por ano de suas quatro marcas.

Investidores como Advent e Warburg Pincus são atraídos por uma combinação única de fatores. Apesar da expansão recente, o Brasil não tem fabricantes ou varejistas que dominem o mercado de moda. As cinco principais varejistas têm apenas 10% de participação de mercado. Há muito espaço para crescer, seja comprando marcas, seja abrindo lojas.

As empresas de moda também têm a vantagem de precisar de pouco capital porque costumam dividir os investimentos na expansão com os franqueados. As margens de lucro de quem tem marcas conhecidas ficam entre 8% e 15%, até cinco vezes maior que em outras áreas do varejo.

Um dos fundos mais agressivos tem sido a Tarpon, que teve um retorno de 500% de seu investimento de 76 milhões de reais na Arezzo. A empresa abriu o capital em 2011. Além da Arezzo, a Tarpon comprou participações em empresas como a Hering, a varejista Marisa e a fabricante de roupas femininas Morena Rosa.

O fundo americano Carlyle comprou, em 2010, 51% da Scalina, fabricantes das meias Trifil. O Gávea investiu em 2011 estimados 150 milhões de reais na Camisaria Colombo, maior varejista de moda masculina, e, em 2012, comprou 30% da empresa de óculos e acessórios Chilli Beans.

A bem da verdade, ganhar dinheiro com moda tem sido mais difícil do que se imaginava. O melhor negócio até hoje foi mesmo o da Tarpon com a Arezzo. Os investidores penam com uma característica comum a muitas empresas do setor — os fundadores são também responsáveis pela criação das peças e acabam mantidos mesmo quando vendem o controle.

Mas eles resistem a medidas, como cortes de custos, que signifiquem uma “intromissão” em seu trabalho, uma senha para brigas com fundos que precisam dar retorno a seus investidores. É uma das dificuldades enfrentadas, por exemplo, pelo fundo Vinci Partners, que em 2008 se tornou sócio da InBrands, grupo com 11 marcas, como Alexandre Herchcovitch e Richards.

A ideia era vender 1 bilhão de reais em 2010, mas a empresa ainda não bateu a marca e deu prejuízo em 2011 e 2012. Áreas como logística e finanças foram unificadas, mas até hoje criação, marketing e vendas estão separados por marca. Sócios como Herchcovitch passaram anos dizendo que é difícil ser criativo pensando apenas em redução de custos. Manter o estilista como sócio pode ser um problema.

Mas sacá-lo pode ser ainda pior. A malharia catarinense Marisol, por exemplo, comprou, em 2006, a grife de moda praia Rosa Chá, do estilista Amir Slama — que depois deixou a empresa. Sem acertar a mão em uma única coleção, vendeu a companhia em 2012 para a Restoque, dona das lojas Le Lis Blanc. A ciclotimia é um dos problemas do setor.

Uma ou duas coleções que não caiam no gosto dos clientes e encalhem nas prateleiras podem colocar o negócio em risco — o que dificilmente acontece com uma fabricante de biscoitos ou de cerveja.

O crescimento do mercado beneficia algumas novatas, mas também companhias que chegam a ter um século de história. A Hering é de 1880. A Malwee, de 1906. A Arezzo, de 1972. A empresa foi fundada por Anderson Birman, na época com 18 anos, e seu irmão Jefferson, de 21. Até os anos 90, fazia de tudo: os desenhos, os moldes, e tinha fabricação própria.

Foi quando um tombo na economia levou a empresa a acumular prejuízos e mudar de estratégia. Naquela época, os baratíssimos sapatos chineses começavam a invadir os principais mercados do mundo. Como outros empresários do setor, Anderson Birman concluiu que seguir naquela trilha seria inviável.

A inspiração para a nova fase veio de dois ícones do consumo. Influenciado pela experiência da Nike, que não fabrica seus tênis e se concentra no desenho e no marketing, Birman decidiu terceirizar a produção para cerca de 200 fábricas e investir o dinheiro na abertura de lojas. Da espanhola Zara veio a ideia de lançar diversas coleções por ano e, com isso, estimular os clientes a visitar as lojas com mais frequência.

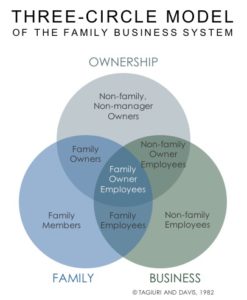

Seis anos atrás, a Arezzo se transformaria na empresa que é hoje. Foi quando recebeu o investimento da Tarpon. Anderson Birman comandava sozinho a companhia. Seu irmão havia deixado o dia a dia, e seu filho, Alexandre, continuava na Schutz, fundada por ele em 1995. A primeira ação dos novos sócios foi coordenar a fusão da Arezzo com a Schutz para acabar com a concorrência familiar (veja quadro ao lado).

O fundo levou também uma cultura de planejamento de longo prazo e de remuneração por cumprimento de metas. De empresa com uma só marca, a Arezzo passou a ter lojas para diversos públicos. A participação de mercado da companhia foi de 4% para 11% em seis anos. “Ajudamos a empresa a ser mais agressiva lançando marcas. Havia um espaço enorme no mercado”, diz Eduardo Mufarej, sócio da Tarpon.

Expansão das marcas

Se o fantástico crescimento da Hering — que nos últimos cinco anos quase triplicou o faturamento — mostrou às empresas do setor a oportunidade que existia na abertura de lojas com sua própria marca, o sucesso da Arezzo a partir de 2007 também deu pistas do caminho ideal a seguir.

No caso da sapataria, a sacada foi investir em inovação e novas marcas. Acostumada a atender consumidores das classes A e B, a empresa lançou em 2008 sua marca mais popular, a AnaCapri, que tem hoje 12 pontos de venda. A grife Alexandre Birman, a mais chique, tem os tais sapatos de couro de cobra.

Hoje, em maior ou menor grau, todas as empresas de moda estão trilhando caminho semelhante. As varejistas mais populares investem para chegar a novos perfis de consumidor. A Renner, que tem mais de 200 lojas pelo país, comprou em 2011 a varejista de utilidades domésticas Camicado e no ano seguinte começou a inaugurar lojas menores em shoppings para vender roupas da marca jovem Youcom, que hoje tem 15 unidades, mas quer chegar a 400 até 2021.

Na Hering, a marca que mais cresce é a infantil Hering Kids, que tem 46 lojas. A empresa anunciou em dezembro de 2013 o lançamento de uma quinta marca, a Hering For You, de roupas femininas. A Riachuelo, que abriu 42 lojas em 2013, investe no lançamento de coleções assinadas por estilistas como Oskar Metsavaht, da marca Osklen, e celebridades, como a cantora Claudia Leitte — assim, consegue atrair todo tipo de gente às lojas.

A tendência de diversificar as marcas começou nos Estados Unidos na década de 80, quando a varejista GAP comprou as concorrentes Banana Republic e Old Navy e se tornou uma gigante que hoje fatura 16 bilhões de dólares. Na Europa, grandes grupos de luxo também são donos de diversas marcas. No caso brasileiro, as redes correm para ocupar, com suas diversas marcas, espaços em shoppings que estão sendo construídos às dezenas nas grandes metrópoles e em cidades médias do interior.

Ao mesmo tempo, as empresas brasileiras se preparam para um inevitável aumento da concorrência com marcas estrangeiras — que há décadas hesitam em abrir lojas no Brasil. Agora, o crescimento consistente do mercado tem aumentado o apetite de um número crescente de multinacionais.

O maior temor dos varejistas nacionais não são os conglomerados do luxo, mas a entrada de varejistas que vendem para a classe média. A GAP inaugurou duas lojas em 2013 e planeja chegar a 15 em cinco anos. A também americana Forever 21, com mais de 500 lojas no mundo, pretende abrir suas duas primeiras unidades no Brasil em 2014, em São Paulo e no Rio de Janeiro.

A espanhola Desigual, com mais de 250 unidades no mundo e presença em 7 000 lojas multimarcas, abriu a primeira loja em São Paulo em novembro e quer chegar a 50 até 2016. “A competição vai aumentar”, diz José Galló, presidente da Renner. “Mas essas redes vão enfrentar dificuldades, já que terão preços salgados se as regras tributárias continuarem como estão.”

Enquanto essas redes começam a chegar por aqui, um número crescente de empresas brasileiras se arrisca no mercado global. Vencer no exterior é coisa rara, e isso vale para empresas de consumo de qualquer país emergente. No último ranking das 100 principais marcas globais, elaborado pela consultora americana Interbrand, há apenas quatro de mercados emergentes: três sul-coreanas — Kia, Hyundai e Samsung — e uma mexicana — a cerveja Corona.

“As empresas tendem a pensar na internacionalização só quando o mercado doméstico desacelera, e pisam no freio assim que as coisas melhoram no Brasil. É um problema, já que para ter sucesso no exterior é preciso investir de forma consistente por pelo menos uma década”, afirma Felipe Monteiro, professor da escola de negócios francesa Insead.

Não é de hoje que empresas brasileiras de moda flertam com a ideia de crescer no exterior. A verdade é que, até hoje, os resultados têm sido pífios. Há duas exceções. A mais antiga é a joalheria H.Stern, que começou a abrir lojas fora do Brasil no fim da década de 40 e hoje tem 30% de sua receita vinda do exterior.

A outra é a Alpargatas, que acelerou o crescimento nas vendas das sandálias Havaianas com uma agressiva estratégia de abertura de lojas. De 2010 a 2013, foram 92 lojas fora do Brasil, em mais de 60 países. Os sinais mais recentes, porém, mostram que as demais empresas brasileiras renovaram suas ambições globais.

O crescimento do mercado nacional nos últimos anos e a associação com fundos de investimento ajudam a explicar essa nova fase. A grife carioca Osklen, comprada em 2012 pela Alpargatas, tem oito lojas em cidades como Tóquio e Nova York (no Brasil, são 69), mas foi apontada por seus novos donos como peça central em sua expansão global no mercado de luxo.

A fabricante de sapatos femininos Carmen Steffens, voltada para o público AB, já tem 45 lojas fora do Brasil. A Chilli Beans abriu 25 pontos de venda no exterior nos últimos dois anos. E por aí vai.

Curiosamente, a atitude dessas empresas pode ser separada em duas — o jeito Havaianas e o jeito H.Stern de crescer no exterior. O primeiro grupo vende uma certa, digamos, “brasilidade”. Osklen e Chilli Beans, por exemplo, apostam nas matérias-primas locais e no suposto jeito brasileiro de levar a vida. Aí vale das tradicionais Havaianas com bandeirinha do Brasil a bolsas de couro de pirarucu, peixe típico da Amazônia, vendidas pela Osklen.

No outro grupo estão empresas que tentam ganhar terreno com produtos mais tradicionais, comparáveis aos criados em qualquer outro país — como é o caso da H.Stern. A Arezzo tenta se encaixar nesse último grupo. “Queremos conquistar clientes não porque somos brasileiros, mas porque fazemos sapatos espetaculares”, diz Alexandre Birman.

A empresa abriu em 2012 uma loja da marca Schutz na avenida Madison, centro de consumo de luxo em Nova York. Também vende, desde 2009, sapatos da marca Alexandre Birman em 50 butiques internacionais, com preços que podem chegar a 1 000 dólares. A empresa já deu seus tropeços tentando crescer no exterior.

Em 2007, apresentou um plano de chegar a 300 lojas na China, mas as chinesas simplesmente ignoraram os sapatos brasileiros. A primeira coleção da Schutz nos Estados Unidos encalhou porque tinha modelos de camurça, totalmente inapropriados para o inverno americano. A empresa correu para reformular a coleção.

Hoje, a loja é uma das campeãs de venda da marca. Alexandre Birman tem ido com frequência aos Estados Unidos. Se a leitora estiver por lá e um estranho ficar olhando para o seu pé em plena Madison, é bem provável que seja ele.